ARTICLES

Female Prisoners and Limitations to Increasing their Representation in Law

Co-Authors

Shafaq Farooq & Zahbea Zahra

DATE

18 November 2021

The article analyzes the evolution of legal representation in regards to the laws governing female prisoners. The insufficient number of female lawyers available and the natural and legal effects resulting from this prospect have been reviewed in order to establish it as a major issue in the prevalence of justice. The Prisons Act 1984 and the Pakistan Prison Rules 1978 have been evaluated to depict how certain provisions have been specifically devoted to women. Additionally, the issues in the accountability procedure prevailing regardless of these legislations have been discussed by considering the defects in the system, and how these prevented women from getting adequate or competent representation in the criminal justice system of Pakistan. For this reason, the prospect of female defendants acquiring legal counsels that can adequately resonate with them amidst rising patriarchal constraints has also been discussed. As such, the analysis continues to infer the consequences resulting from lack of female lawyers by diverting attention towards the obstruction of their rights in light of due process, autonomy and rule of law. In this way, a nexus between the constitutional provisions and fair trial and access to justice has been explored. Moreover, the article uses an integral quantitative element to observe the notion of legal representation for female prisoners according to members of the legal fraternity. The analysis concludes by suggesting reforms and promoting women’s representation in law.

Introduction

Lack of legislation and legal instruments are not the main obstacles in women attaining equal representation in law. Rather, the defects in our society and official systems regulated by the State appear to be troubling points of origin; the laws and legal system house numerous issues for female defendants and convicts in the country, and these do not adequately protect them from suffering unnecessarily for their basic human rights such as the right to fair trial, the right to be equally represented etc. The problem of laws not being implemented properly and hence failing to protect women is an alarming issue in today’s era. As such, this notion is extended to female prisoners in Pakistan as well, and the following analysis addresses the atrocities endured by them on account of lack of sufficient representation in law.

Evolution of laws governing legal representation of female convicts

The process of women getting convicted for a crime and being sentenced to imprisonment is not a new or opposed concept. Despite the existence of laws to protect female accused and convicts confined in Pakistani jails or prisons, newspaper articles and videos on media channels have shown that female prisoners have been exposed to unjust treatments. This is because the implementation of the laws particularly drafted to increase legal representation of female convicts can be criticized and challenged. The reason is simple; they are not implemented in their true sense and to reflect the purpose for which they were created.

National laws

The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (1956), the supreme law of the country from March 1956 to 1958 until the coup d’état, deemed every citizen including women to be entitled to “equal protection of law” and that no person shall be arbitrarily deprived of their life or liberty. It further continued to provide all prisoners, regardless of their gender, the right to “due process of law” and “autonomy”. The Prisons Act (1894) and Pakistan Prisons Rules (1978) were legislated to state that no prisoner could be imprisoned except under a lawful warrant or order issued by a competent Court. The Pakistan Prison Rules further prescribe that search and examination of women prisoners shall be carried out by a female warden under orders of Deputy Superintendent or Medical Officer.

The current Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (1973) ensures that every citizen living in Pakistan shall be given the “right to fair trial” and that “access to justice” must be assured for every individual living within the territory of Pakistan. Moreover, the Constitution further states that no discrimination shall be made in terms of enforcement of rights and duties with regards to sex or gender. The purpose of including such a provision within the supreme law of the land is to maintain accountability and equal protection of all citizens in accordance with the ambit and regulation permitted by the law. For the regulation of right to due process of law, the “right to appeal” and petitions against conviction is also provided to male and female prisoners under Chapter V of Pakistan Prisons Rules (1978). Furthermore, to ensure that ‘rule of law’ prevails, the Criminal Procedure Code 1898 (CrPC) provides a process for appeal when the appellant is in jail so that the right of access of justice is available to convicts at all times during his/her incarceration.

International laws

Pakistan is a signatory to various international conventions and treaties which were established to provide protection to individuals living in prisons. To analyze how international human rights related to female prisoners are being violated in Pakistan, one may retreat to basic human rights. The Basic Principles for Protection of all Persons under any Detention or Imprisonment (1988) states that all persons deprived of their liberty and who are convicted for a crime shall not be ill-treated, and their inherent “right to dignity” shall be protected at all times. However, here in Pakistan there are sufficient examples to witness how the protection of ‘right to dignity’ is not ensured for female prisoners and despite having laws for protection and safety, women prisoners are more or less subjected to violence, oppression, and exploitation in prisons. On the basis of research carried out by Khushboo Ali Bhagri on 29th November in year 2010 on “Women Prisoners in Pakistan: A Case Study of Rawalpindi Central Jail”, it is safe to say that female prisoners are subjected to ill-treatment and sexual harassment during their confinement in Rawalpindi Central Jail. Such violations of basic human rights paint a clear picture of how various international human rights enforceable through international conventions and treaties are not being properly implemented in Pakistan.

In order to evaluate Pakistan’s duty to ensure basic human rights for female prisoners, one may refer to the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR), the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) since Pakistan is not only a signatory to these international conventions but has also ratified them. These international conventions state that all individuals are “equal before law” and that they shall be entitled to protection of law without ‘discrimination’. Considering that the UDHR carries the essence of customary international law, these principles should be extended to all areas of law. These can be interpreted to infer that women prisoner should not suffer discrimination, and that they should be protected from all forms of violence and exploitation. In Pakistan, however, issues of discrimination, violence and sexual abuse against women in prison have occupied a noticeable place in our history.

Moreover, international law provides all prisoners, including female inmates, a basic “right to an adequate standard of living” . Contrary to this standard, prisoners in general and female prisoners are specifically deprived of basic life necessities and live in poor conditions. For example, they receive inadequate medical care, rehabilitation policies are questionable, and they often end up being mistreated in the prisons. Overall, one may consider that in accordance with national and international law, female defendants and convicts are entitled to certain protections and basic fundamental and human rights in order to increase their legal representation in law through acts, statutes and conventions. However, the issue of non-implementation or poor enforcement of such laws acts as obstacles in increasing legal representation of female convicts suffering in various prisons throughout the country.

Reasons for female prisoners’ inadequate representation in law

The need to make the legal fraternity more gender inclusive serves the crucial purpose of bridging the wide gap towards attaining an equal number of female lawyers. Additionally, it would also contribute to achieving an overall progressive society based on both equality and equity. Since the legal field in Pakistan is male dominated and accompanied by many patriarchal features, the interplay between the two can be considered to be one of the most significant reasons for the lack of women’s representation in law. This is because male dominance and patriarchy present an obstacle which derives its power from the society; in this way, the society itself prevents women from adequately accessing justice. Having a sufficient number of female lawyers gives female prisoners going through the procedure of law enforcement a more viable chance of getting a legal representative who has a greater chance of resonating with them. A competent female lawyer may be able to present a better shield as compared to her male counterpart, who may not be able to provide the same effective services owing to the cultural, religious and political boundaries of segregation that are currently prevalent in the country. The United Nations reinforced this notion on a similar account because it can help in making the criminal justice system more accessible for women .

Patriarchy and gender discrimination

Patriarchy and male dominance are two interconnected factors that prevent females from embracing litigation actively. For instance, despite the legal education and competence of many young law students and fresh graduates, they may be subjected to sexism or other forms of discrimination in firms or courts – a factor that may contribute in societal constraints whereby many feels that it is unsafe for women to go to court on a daily basis. Indeed, many female lawyers have attested that they have been discriminated against on the basis of their gender. Advocate Fatima Khan pointed out “harassment, intimidation and discrimination” to be some of the issues female lawyers are forced to endure. One may consider writer and advocate Zainab Z. Malik’s account to be relevant here; she revealed how she and her colleagues had been badgered by an older male lawyer until she accepted a book about recipes and how working women posed a danger to their children. So while Article 25 of the Pakistani Constitution directs that discrimination on the basis of sex is prohibited, such discrimination operates under our nose on a daily basis. Since such instances paint the legal fraternity with a negative form, women are discouraged from entering the legal field. While safety is usually the most commonly heard ground to support this notion, the underlying thought of a woman doing something akin to an allegedly established “man’s role” is also a common concern for those thriving from the benefits they receive from patriarchy. Therefore, when female lawyers are prevented from entering and excelling in the field, it incidentally limits the options available for female prisoners since they do not have many available avenues left for them. Hypothetically, for instance, a female victim who has suffered at the hands of a male perpetrator may be unable to communicate or reveal the details of the ordeal to a male lawyer because of the emotional and psychological trauma. This factor would then incidentally curtail the means of representation available to her. Thus, it encourages the belief that is crucial for our bars to house more competent female lawyers, especially when it comes to criminal law.

Structure of the legal fraternity

The pioneering community of our legal fraternity is primarily male dominated. In this way, the discrimination can be traced to the most influential platforms in the system. In 2013, the Asian Human Rights Commission pointed out that out of the 103 judges in the superior courts, only 3 were female – such a statistic indicates Pakistan to be in breach of the obligation it owed under the UN Beijing Conference in 1996. This standard required 2.91% to be 33%. Today, while Pakistan has finally welcomed its first Chief Justice of the Balochistan High Court with Honourable Justice Tahira Safdar, The country still has a long way to go. This much is evident by how the seat of a justice of the Supreme Court is yet to be honoured by a woman. The same notion is extended towards female lawyers in the legal fraternity. Since the system has yet to evolve its structure to make itself completely accessible and convenient for female lawyers, our courts have still not housed an adequate number of female lawyers. Therefore, such a notion begs the absurd question of whether the system deliberately avoids paving an accessible and convenient path for women to thrive in the legal field or if female lawyers are simply unable to reach a standard where they can match the competence of their male counterparts – a notion which is obviously untrue and something that should be proven in practice.

In turn, this situation has had a dire effect on female prisoners. For instance, let’s consider a hypothetical example of girl named Aliya. Aliya is a female prisoner who has allegedly and accidentally killed Bashir, a man in her community, while defending herself from Bashir’s attempt to rape her. Being from a financially impaired background and so having no choice but to accept Kareem, a public defense attorney, as her legal counsel, the rational fear and discomfort towards men prevents her from conveying the details of the events to Kareem properly. This is where we can issue the first strike. Moving on, Kareem unfortunately turns out to be an incompetent lawyer who takes the little money Aliya and her family can offer, but does not exert any effort to establish a self-defense claim. This is where we establish the second strike. The judge does not pay heed to Kareem’s obvious incompetence, and sentences Aliya to spend the rest of her life locked in a prison under the alleged persona of a coldhearted killer. Considering how easy it was for Kareem to make some money for himself, he focuses on similar rape cases and making himself a fortune, and ends up allowing ten more rape victims to be imprisoned for life, and so on. Here, we have our third strike. While considering this example, one notes how the lack of a proper enforcement and accountability mechanism is such a dire systematic defect that it ensures a domino effect which amplifies injustice at all stages. Whether it is the rule of law itself or the principles of natural justice, such a defect illustrates a crack in the system that ends up contributing to oppression, persecution and violation of human and fundamental rights rather than simply being a lawful prosecution. In this regard, some cases, like those revolving around sexual and/or other physical abuse, require prosecutors to be gender sensitized in order to access justice in its purest form.

Socio-economic factors

The Cornell Center on Death Penalty Worldwide has reported that most female prisoners who are being held on death row charges are those originating from the lower social economic strata of the community. This means that they cannot afford to pay for private or better representation. Since they are not sufficiently literate, they may not be able to defend themselves properly because the lawyers appointed by the state may not be adequately competent or trained, or they may simply not be able to handle the excess workload. For instance, in 2013 a research revolving around 100 women prisoners across the country showed that 54.4% of the prisoners in the Larkana and Sukkur prisons had no lawyer, and some inmates had either never met their lawyer or the ones who did manage to secure one by the State were able to do so after six or more months. Hence, if a female enters the arena of drug trafficking to meet basic ends, is it reasonable or just to allow her to suffer more than what her crime merits, just by virtue of her not being able to afford a competent or private legal counsel? One may refer to the example of Shagufta Iftikhar v The State, where an FIR revealed that a veiled woman had been involved in a dacoity. There was no means to identify the accused conclusively, and the accused was able to get bail after remaining in police custody for a year and a half without any proof and representation. There was no trial, nor was there any hint of one commencing any time soon. With this, we once more return to the issue of state responsibility, and the need to evolve our justice and education system to produce competent female lawyers.

Moreover, since the majority of the accused or convicted women are illiterate , a mere accusation originating from a social disagreement can allow them to suffer an indefinitely long time in prison. While the law itself requires for the accused to be presented before a magistrate within twenty-four hours, this notion is not always strictly followed. Since such victims of unlawful detention are unaware of their legal rights in the first place, and they have no competent legal representative to present their case, it gives way to a chain of unnecessarily unjust imprisonment sentences. For instance, a woman who was accused of killing her husband by her in-laws with the alleged intent to get her children’s custody was not only locked up for over a year but also had to endure abuse and torture for a confession. She could have been protected from such heinous acts had she been given proper legal representation in the first place.

Survey analysis and Pakistan Prisons Rule (1978)

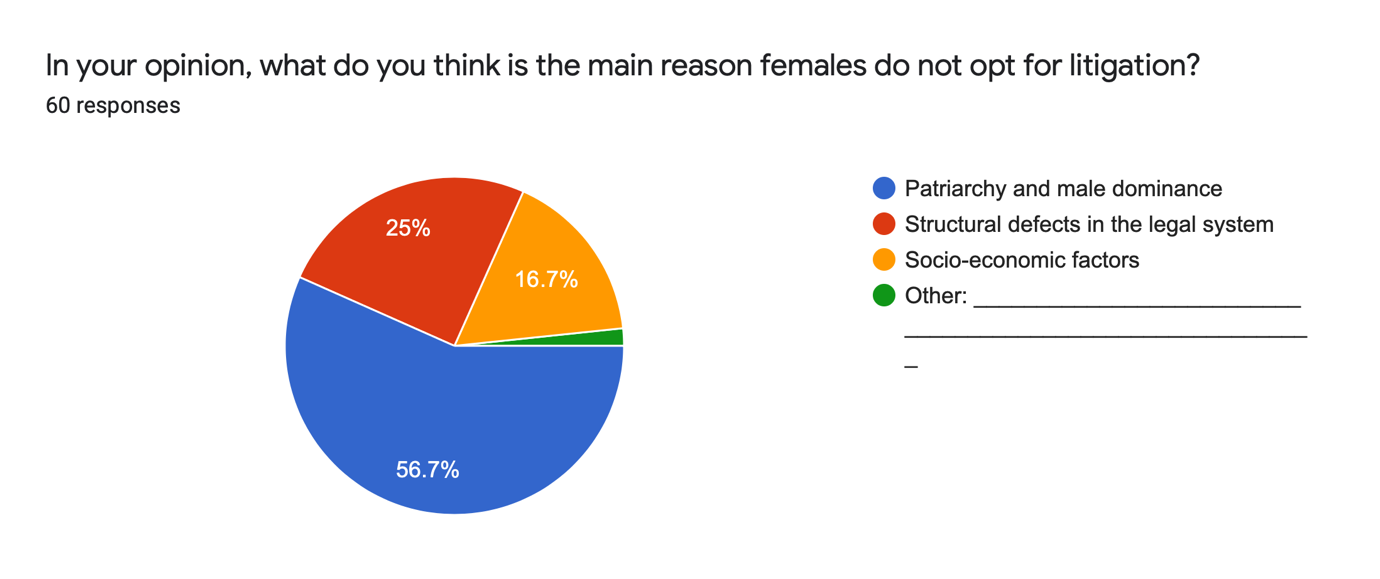

We conducted an online survey in which sixty individuals were asked about their perception and awareness about the obstacles in female prisoners’ representation in law. 51.7% of the respondents with a legal background were not aware that the Prisons Act 1984 and the Pakistan Prison Rules (1978) dedicate separate provisions for female inmates to cater to their needs. It further concluded that 56.7% persons consider patriarchy and male dominance to be the ultimate reason why females do not opt for litigation. On the other hand, 25% considered that structural defects in the legal system and 16.7% considered socio-economic factors to be the major obstacles for women opting litigation in the country. Considering these, it is crucial for the Pakistan Prison Rules to ensure female representation in prisons keeping these obstacles in mind – the rules should be amended so as to counter deep-rooted issues like patriarchy and socio-economic imbalances from depriving women of their legal rights.

According to the survey, 21.4% people considered limited representation for female convicts and defendants, 12.5% perceived issues in procedural accountability, and 8.9% believed issues of female autonomy and limited number of female lawyers to be major hindrances in the practical application of the Prisons Act 1984 and Pakistan Prisons Rule 1978. However, 57.1% individuals contemplate that all of these can be perceived as a combined issue in the practical application of the abovementioned laws in Pakistan regarding female convicts and defendants.

Moreover, on the basis of the verdict given by these respondents, inadequate representation of female convicts before law contributes to the instability of the judicial setup. This is valid to the extent that it emanates the notion that a body obligated to play an essential role in the prevalence of justice is unable to do the task for which it was created. Hence, equal representation should be given to female prisoners before law to cater their needs fairly and justly in order to overcome this problem.

According to the survey, 77.2% of the individuals were aware that gender stereotypes affect women prisoner’s representation before the law and 85% people think that lack of female lawyers is an issue that results in obstructing the fundamental right of fair trial and due process of female inmates. Therefore, feasible methods must be adopted to increase the number of female lawyers so that female prisoners can exercise the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution of Pakistan, 1973.

After scrutinizing the Pakistan Prison Rules (1978), one may consider that the rules do not adequately cater the needs of women prisoners nor do they specifically address certain common issues faced by women prisoners. The major problem being that the Pakistan Prison Rules (1978) have been drafted with a male centric lens which heavily focuses on the issues faced by male prisoners instead of providing an equal representation to all genders before law. Moreover, it does not provide a review mechanism to make sure that no violence is being conducted against female prisoners and their rights are protected instead of being abused by Investigating Officers (I.O), female/male wardens and other inmates during their time of sentence.

The defects in the Prisons Act 1984

While the Prisons Act 1984 has dedicated specific provisions to women, these may still appear to be insufficient. The legislation still appears to be unsuccessful in completely addressing the struggles female prisoners endure in prison. This is because the law does not address the importance of ensuring the basic human rights of the inmates and the relevant special requirements, and does not prescribe prevention measures against the atrocities committed against the inmates. Leaving them with scarce autonomy, female prisoners practically have no chance of explaining how they have been subjected to an alleged offence to a court of law because the very prospect of representation available for such purposes is an unlikely and questionable reality. For instance, while female prisoners in Punjab may present their claim before the Learned Sessions Judges or the Inspector General of Prisoners, the intervening factors in the journey to reach this step may prevent them from doing so. Similarly, while official visits may be done to address female prisoners’ complaints, the law itself is yet to dedicate special regulations for complaint registration.

No provision for legal representation

While the Act lays down many details for the governance of the prison, it does not provide a proper mechanism for a prisoner to follow in order to register a complaint. For instance, while the Act regards the Medical Officer to be responsible for the “sanitary administration” of the prisoner, it does not provide any road that may be followed if the Officer fails to perform his duties. Even if a prisoner did know that she has a valid ground for a complaint – an unlikely factor owing to illiteracy and lack of awareness – fear of the authorities may prevent her from raising her voice. Likewise, if a female prisoner endures abuse, there is no mechanism enshrined in this Act in order to acquire justice for her. In this way, with complete lack of representation within the prison, the cycle of injustice continues. In Maria Sanam v The State, For instance, the accused had been kept in a prison for nine and a half months, and no legal counsel had been able to prove or disprove her involvement in the alleged crime. Such a long duration of imprisonment continued until it was eventually brought to notice for bail purposes. Similarly, in Mst. Fauzia Haveed v The State , the accused had been detained in a prison for six months on account of delays in her trial. The delays could not be attributed to her, and there was no remedy available for her to pursue in prison during this time. She was eventually granted bail.

Section 14: Duties of the Medical Officer

Section 14 prescribes that whereby the Medical Officer, who should be a female in order to address the comfort and dignity of the female prisoner, reasonably believes that a prisoner has been subjected to a discipline or treatment that has had a detrimental effect on the prisoner’s mental health, then it must be reported to the Superintendent in writing with anything else that she deems appropriate in support of his claim. Since these instances are reported by the Medical Officer to the Superintendent, there is nothing to ensure that the female convict’s injury will qualify as grave enough to be reported by him. Even if it is reported to the Superintendent, the matter may or may not be reported to the Director of Prisons. Such a long chain based on hierarchy and discretion of one superior officer after the other rather than the gravity of the alleged injustice endured by the female prisoner are likely to prevent any chance of accountability and representation. For instance, proposing that the Superintendent will acquire a legal representative to present the female convict’s case is definitely a stretch. In 1992, two women had been tortured in a police station while they were waiting for their trial in Kot Lakhpat Jail; they had no means to get the attention of legal authorities and the ordeal they faced was only brought to notice after their lawyers visited them a week later. Even though the Senior Woman Medical Officer confirmed their injuries, she did not report them to higher authorities. Eventually, the Magistrate’s report denied the incident as well, and the complaint was not even investigated since there was no one to represent them. In other cases, alleged presence of corruption may prevent an officer from reporting the case. Keeping this factor in mind, the imprisonment authorities may themselves serve as a hurdle in a female prisoner’s representation despite the existence of this provision. This is considering that a female inmate is unlikely to have substantial social and financial support from the outside world, and so would be unable to acquire a counsel, or an independent and impartial body to review her grievance.

Section 27: Separation of prisoners

This provision instructs that whereby a prison accommodates both men and women, females are to be kept separate from the male inmates in order to prevent them from seeing, touching or talking to each other. Contrary to this provision, many instances emerge whereby the female prisoner is kept in supervision of a man, and this factor ends up being injurious to her mental and physical health. Since prison authorities are the most likely perpetrators behind the issuance of such an act in the first place, a female prisoner is unlikely to be able to claim relief for this. While the provision enshrines the notion of segregation without any exception, the absence of any penalty for the perpetrators or possible relief for the victims prevents the regulation from being applied strictly – power play, intimidation and other evils may be frequent contributors behind such infringements.

Section 46: Punishments

Section 46(12) directs that female or civil prisoners cannot be punished with handcuffs, fetters or whipping. One may appreciate this factor since had this restriction not been penned, the possibility of exploitation and lawful torture might have emerged as well. The ban of this punishment does give a hint towards the cruelty of this punishment, and may be considered in future reforms and possible prohibition of this punishment as a whole. Despite the discussion about reforms in this area, the fact that there is currently no independent complaint registration process gives way to the potential of such punishments occurring under a concealed cover. In September 1992, two female prisoners claimed to be punished in a torturous way; one of them was restrained and beaten with leather thongs for a night while the other miscarried as a result of a vicious beating. This provision presents a classic opportunity for the law to recognize any violation of the provision to be custodial abuse that automatically entitles victims to legal representation.

Consequences resulting from lack of female lawyers

Due to the lack of female lawyers in the legal profession, female prisoners face a lot of adverse consequences that act as a barricade for them in obtaining or securing justice. Various factors like patriarchal constraints, limited representation for women in law, societal/family pressure, non-availability of equal educational opportunities for females and several other reasons lead us to a world where despite the advancements of the 21st century, female convicts have to suffer from violation of their basic fundamental rights due to lack of female lawyers. It can be said that female prisoners resonate and trust female lawyers more with the personal accounts required to present any defense against the alleged offense against them.

Violation of the equal protection clause

The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (1973) states that all citizens are equal regardless of their gender and are entitled to equal protection of law. Moreover, in the case of Akbari Begum v The State, it was observed that fundamental rights in regard to justice and fair trial shall be guaranteed and all citizens regardless of their gender shall be given access to justice. However, scarcity of female lawyers, who are more likely to be trusted by female prisoners in order to reveal the private information crucial to their case, poses a serious hurdle in their path towards access to justice and being protected by law as every other individual. In Pakistan, male convicts have a better chance of representing themselves due to the judicial system providing a comparatively more convenient environment owing to it being largely male dominated and the massive availability of male lawyers. Whereas due to lack of female lawyers, female prisoners are more hesitant towards sharing their personal information with a male lawyer due to the mindset of the society we live in and due to the lack of quality education as well. As a result of which, unfortunately, female prisoner’s right of getting equal representation before the law gets infringed in the country.

Obstruction of right to fair trial and due process

The right to fair trial is a fundamental right according to which every citizen living in the country has a right to defend themselves in a situation where any civil or criminal charge is brought against them, in a just/fair trial before a competent court of law. However, this fundamental right gets constrained because of the lack of female lawyers who could represent female convicts in courts to make sure fair trial is being conducted and the female convict’s right to due process of law is safely protected. In NuzhatShoukat v Superintendent, Central Jail, Karachi, The female defendant after being convicted by the trial court was unable to file an appeal or petition for mercy in the higher courts due to non-availability of competent women lawyers and lack of proper female representation in law. Hence, this can be perceived as an example of obstruction of a female convict’s right to acquire justice at all levels. Moreover, due to other factors such as societal pressure, norms and religious restraints most of the women prisoners do not consider consulting a male lawyer alone or independently as an appropriate resort which prevents them from proceeding to further stages of fair trial and due process of law.

Curtailment of the right to privacy

The Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam, signed and ratified by Pakistan in August 1990, affirms that everyone shall have the right to live in security for themselves, their dependents and their honor. Moreover, every individual shall have the right to privacy in the conduct of their private affairs and should not be placed under surveillance to besmirch their good name. In this manner, every female prisoner has a right to privacy according to which she should not be placed under scrutiny which could harm her reputation by sharing private information regarding some previous affairs. However, as a result of lack of female lawyers, the right of privacy of female prisoners gets curtailed when they have to share facts of a case with male lawyers whom they cannot trust with deeply personal information and fear that her good name/reputation would be harmed due to presence of various stigmas in society. Since this information is often used against her publicly in a court of law, female prisoners’ hesitance towards revealing this information is merited.

Importance of female prisoners’ right to legal representation

Ensuring that female prisoners can easily register a complaint before the law is crucial because it promotes a system of checks and balances by ensuring that the officers who exercise sufficient control over them do not get a clean chit where they act beyond their powers and at the expense of the female prisoners. In this way, female prisoners’ representation ensures accountability. It is important to define an express, clear and independent system for female prisoners to be represented before the law in order to eliminate instances revolving around custodial violence, unjust punishments, lack of basic facilities such as sanitation, clothing, educational or rehabilitation opportunities etc. For instance, male juvenile convicts are not kept in the same vicinity as older male convicts, but the same approach is not adopted for female juveniles and adult female convicts. It was access to legal representation that allowed this change in the male imprisonment system. Hence, if female inmates are sufficiently represented before the law, Pakistan may be able to see the possibility of raising the standard of its prisons to one that is deemed internationally acceptable.

Legal reforms

The limitations regarding female prisoners’ representation in law should be addressed immediately by the entire machinery of the state. In furtherance to this notion, responsibility must be divided amongst each organ of the state. Since the issues female prisoners face regarding their representation in law is largely dependent on gender-based factors seeping into areas like cultures, norms etc. it is crucial for lawmakers to ensure that women are primarily involved in the concerned law-making.

Eliminating gender discrimination in the legal system

Gender discrimination can be countered by initiating gender sensitivity trainings for both judges and lawyers. Senior lawyers should shoulder the responsibility of training female lawyers so that they can proficiently appear in a court of law to argue for their client; their role should not be limited to research work. Moreover, associated gender stereotypes should be discouraged and likewise, general gender stereotypes should be prohibited in the workplace. For instance, legal employers often tend to ask female lawyers about their plans to get married , have children or other domestic roles while interviewing them for a job. Such practices should be prohibited as they do not reflect the applicant’s competence in any way.

Proper legal education and training

Legal education and training programs should step away from majorly theoretical content. Special gender sensitivity training program should be introduced where future legal practitioners are taught how to practically handle gender sensitive cases with the help of practical examples and exercises. It is extremely important to discourage toxic competitiveness, patriarchy and gender discrimination currently prevalent in the system since these contribute to widening the gender-based gap in the professional arena. Legal education system should be evolved to ensure a proper grading system which is not purely reliant on rote learning or memorization, and female law students and fresh graduates should be given equal opportunities at all stages. Not only should senior lawyers lean towards investing significant time to training female law students and fresh graduates, but they should be expressly recruited in order to break the current taboos so as to set an appealing precedent for future generations.

Special efforts to fix structural defects

Fixing structural defects in the system will allow the justice system to improve female prisoners’ representation in law. This would mean that the system is ensuring complete implementation of the law with an effective and unbiased accountability mechanism in place. It would place a special responsibility on the esteemed members of the legal fraternity to make the justice system more accessible for female prisoners, and reject any issue that obstructs their representation in law.

Counter cultural impediments

Discriminatory norms and practices promoting women’s inferiority and subordination have become so common that they are now accepted as a part of our cultures and traditions. Therefore, female inmates may accept their fate even where there is substantial room to prove their innocence; their acquaintances outside the bars of the prison would be ready to reject them on their possible return on account of the negative attention arising from such societal norms. This can be reasoned by how once women are stamped as inferior, any attention diverted to them is likely to be accompanied by criticism and social exclusion. Hence, unless such deep-rooted taboos are rejected in order to ensure that all female prisoners from any class and region of the country are free to strive for their rights, Pakistan’s justice system will continue to lie under a dark cloud.

Body to objectively review violations

An independent body should be formed by the Federal Government to ensure that female prisoners are adequately represented before the law. This body should operate beyond the control of a prison superintendent and any other prison staff member. It should assess each prisoner’s case separately. For instance, if a female prisoner’s trial has been delayed by an abnormally long time due to lack of representation, the injustice should be rectified immediately. If the prisoner’s case is related to a sexual offence, and she is unable to communicate with a male lawyer or the lawyer is unable to provide their services in a competent manner, it should result in immediate replacement with a competent lawyer. If an objective assessment proves that the lawyer is unable or unwilling to represent the convict for her benefit, and instead intends to exploit the client financially, immediate replacement or accountability proceedings should be initiated.

Prevent socio-economic reasons from contributing in lack of legal representation

If the system is able to provide competent lawyers for female prisoners, they will not need to rely on their private pockets to be adequately represented before the law. Additionally, their privacy should be upheld in order to prevent social exclusion or other stigmas arising from cultural stereotypes. This is because these women are unwilling to opt for any option that attracts attention to them, and reforms in this area will allow them to access justice without infringing their dignity.

Awareness about legal rights

Majority of the female prisoners are unaware about their legal rights. The responsibility for this can be traced back to the prevailing education system and the operation of the imprisonment systems. Not only should schools incorporate knowledge about legal rights in their curriculums, but every prison should be held responsible for educating prisoners about their relevant rights. For instance, a female prisoner should know that being abused in custody entitles her to representation before the law in order to lodge her complaint. She should know that the State is responsible for providing a competent lawyer for her if she cannot afford one on her own. More importantly, she should be aware about the duties her legal representative owes to her, and so on.

Conclusion

Conclusively, after scrutinizing the current laws dealing with female defendants and convicts in Pakistan, one may infer that the notion of women prisoners facing extraordinary challenges while attempting to get legal recognition is a merited claim. There are plenty of factors that make them suffer miserably in the process of seeking justice. Among all the other reasons, it is worth mentioning that female convicts do not get an equal chance of representation in law due to lack of availability of female lawyers competent enough to take their case. Through the survey conducted, it can be concluded that female convicts resonate and trust female lawyers more with their personal information as compared to a male lawyer, who they think is likely to mock or exploit them at any stage of the case. Other than this, societal pressure, patriarchal constraints, socio-economic reasons, defects in the legal system and lack of educational opportunities also prevent women from acquiring autonomy and equal representation in law. Therefore, it is important to reform our justice mechanisms in order to make remedies adequately accessible. For this purpose, a few reforms have been highlighted among which providing proper legal education, training to female convicts and elimination of gender-based discrimination in the legal system are the most important as they have the potential to make a difference in the society by increasing women representation in law.

Table of Authorities

Cases Akbari Begum v The State [1985] PLD 123(LHC) Maria Sanam v The State [2017] MLD 1373 (LHC) Mst. Fauzia Haveed v The State [2009] YLR 664 (IHC) Nuzhat Shoukat v Superintendent, Central Jail, Karachi [1992] PLD 108 (SHC) Shagufta Iftikhar v The State [2018] MLD 531 (LHC)

Statutes Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1956 Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973 Criminal Procedure Code, 1898 Pakistan Prisons Rules, 1978 The Prisons Act, 1894

Bibliography

International Instruments Basic Principles for Protection of all Persons under any Detention or Imprisonment, 1988 Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam, 1990 Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, 1979 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966 Universal Declaration on Human Rights, 1948 United Nations General Assembly, A/RES/67/187 2013

Journal Articles

Ali Bagri K, ‘Women Prisoners in Pakistan: A Case Study of Rawalpindi Central Jail’ (2010)

Cornell Law School, ‘Judged for More than Her Crime, A Global Overview of Women Facing the Death Penalty’ (A Report of the Alice Project September 2018)

Corrieri L, The Law, Patriarchy and Religious Fundamentalism: Women Rights in Pakistan’ (Asian Legal Resource Center 2013)

Muhammad Baloch G, ‘From arrest to trial court: the story of women prisoners of Pakistan’ (2013) 91 Procedia –Social and Behavioral Sciences

Research Reports

Amnesty International, ‘Women in Pakistan: Disadvantaged and Denied Their Rights’ (1 December 1995)

Human Rights Watch, Pakistan: Poor Conditions Rife in Women’s Prisons New York: US. (2020)

Report by the Commission, ‘Prison Reforms in Pakistan’, (Islamabad High Court in W. P. 4037 20 2020)

Newspaper Articles

Ali Shah S, ‘Justice Tahira Safdar sworn in as first woman chief justice of a Pakistani high court’ Dawn (Balochistan 1 September 2018)

Alvi S, ‘Pakistani convicts teach inmates their legal rights’ Al Jazeera (Karachi 23 May 2018)

Bukhari A, ‘Why do we need more women in law?’ Express Tribune (Karachi, 9 July 2020).

Jawziya F. Z and Sara M, ‘Can the women of law get justice?’ Dawn (Karachi, 7 October 2018)

Malik Z, ‘Skirt lengths and bhuna gosht: What women in Pakistan’s legal fraternity face’ Dawn (Lahore 10 March 2020).

Rizvi Y, ‘Women’s prisons: A feminist issue’ Dawn Prism (25 June 2019)

Siddique Khan A, ‘Feminisation of law and judiciary in Pakistan’ Express Tribune (13 September 2020)